Craseonycteris Thonglongyal

The 6-inch Craseonycteris thonglongyal bat weighs only 0.06 ounce. Yet it has all the multiplied thousands of specialized organs that every mammal has. How can this be? Evolution could not produce it.

Blackpoll

Blackpoll Warbler

The blackpoll warbler weighs only three-quarters of an ounce; yet twice each year it flies 2,400 miles [3752 km] non-stop for 4 days and nights. These little birds spend the summer in Alaska and then, in the fall, on one day they all know to begin flying eastward. Arriving in New England, they head out over the ocean for a non-stop journey. Climbing high in the air, and quickly becoming separated from one another, they climb higher in the sky. Although they want to go to South America, they begin by heading toward Africa. Climbing to 20,000 feet [6096 m] in the sky, they head off. How can each bird keep warm at such a high altitude? There is very little oxygen for it to breath, and it is so much harder to fly when its tiny wings must beat against that thin atmosphere.

Yet on it goes, with nothing to guide it but a trackless ocean below and sun, stars, and frequently overcast sky overhead. At a certain point,the little bird encounters a wind which does not blow at a lower altitude. It is blowing toward South America. Immediately, the little bird turns and goes in that direction. It had no maps, and no one ever instructed it as to the direction it should take. Well, you say, it may have taken the trip before. No, this might be one of this year’s new crop of birds which hatched only a few months before in Alaska. And its parents never told it what it was to do. Now, alone, separated from all the other birds, it keeps flying. It cannot stop to rest, eat, or drink. It dares not land on the water; for it will drown.

A Bronze Bird

Many other examples could be cited. One is a bronze bird in New Zealand which abandons its young and flies off. In March, when strong enough to fly, they follow after, taking the same route: first 1250 miles over open sea to northern Australia: then to Papua New Guinea; then the grueling distance to the Bismark Archipelago – a migration of 4000 miles from New Zealand where they hatched not long before.

The Bat

Specialized features enable the bat to fly, yet all those features had to be placed there together in the beginning. Its pelvic girdle is rotated 180 degrees to that of other mammals. That means it is backwards to yours and mine. The knees bend opposite to ours also. This ideal for bats, but an impossible situation for evolutionary theory to explain. The pelvis, legs, knees and feet of a bat are structured so that they can sleep, while hanging upside down at night from rocks and trees.

Young bats have special infantile teeth with inside tooth hooks on them. These allow the immature bats to hold onto the thick hair on their mother’s shoulders. Without those juvenile teeth, few bats would survive to adulthood. It would be equally hazardous to the bat race if the babies lacked the awareness to grip the fur with their teeth.

The radar abilities of bats surpasses man’s copy of it. In a darkened room with fine wires strung across it bats fly about and never touch them. This is called “echolocation,” but the bat was never taught the word.

Oilbird

Sounds like a tortured man; name comes from a time when the chicks were boiled to make oil.

A true bird, the oilbird, also uses radar to fly in and out of the caves. So do porpoises and whales, but theirs is called “sonar” instead of “radar.”

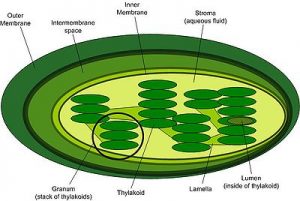

Scientists estimate that over 400 million-million horsepower of solar energy reaches the earth every day. Photosynthesis is the process by which sunlight is transformed into carbohydrates (the basis of all the food on our planet). This takes place in the chloroplasts. Each one is lens-shaped, something like an almost flat cone with the rounded part on the upper side. Sunlight enters from above.

Scientists estimate that over 400 million-million horsepower of solar energy reaches the earth every day. Photosynthesis is the process by which sunlight is transformed into carbohydrates (the basis of all the food on our planet). This takes place in the chloroplasts. Each one is lens-shaped, something like an almost flat cone with the rounded part on the upper side. Sunlight enters from above.

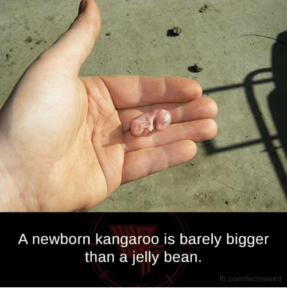

The marsupials are the pouched mammals. Two of the best-known are the American opossum (the only marsupial in North America) and when it is born it is no larger than a tiny bean! It is blind, deaf, hairless, and looks somewhat like a tiny worm. A newborn opossum is smaller than a honey bee, and six will fit in a spoon. There are 12-15 in each litter.

The marsupials are the pouched mammals. Two of the best-known are the American opossum (the only marsupial in North America) and when it is born it is no larger than a tiny bean! It is blind, deaf, hairless, and looks somewhat like a tiny worm. A newborn opossum is smaller than a honey bee, and six will fit in a spoon. There are 12-15 in each litter. Down into the pouch it goes, and there it fastens onto a nipple. Immediately, the nipple enlarges, locking the tiny creature to it. There it remains for many months as it grows.

Down into the pouch it goes, and there it fastens onto a nipple. Immediately, the nipple enlarges, locking the tiny creature to it. There it remains for many months as it grows. The mallee bird lives in the Australian desert. In May or June,l with his claws, the male makes a pit in the sand that is just the right size: about 3 feet [9 dm] deep and 6 feet [18 dm] long. Then he fills it with vegetation. As it rots, it heats up. The bird waits patiently until the rains, which increase the heat to over 100º F [38º C] at the bottom of the pile. The bird waits until it is down to 92º F [33º C].

The mallee bird lives in the Australian desert. In May or June,l with his claws, the male makes a pit in the sand that is just the right size: about 3 feet [9 dm] deep and 6 feet [18 dm] long. Then he fills it with vegetation. As it rots, it heats up. The bird waits patiently until the rains, which increase the heat to over 100º F [38º C] at the bottom of the pile. The bird waits until it is down to 92º F [33º C].